Accidents and A-levels

This crisis was foreseeable

A book that I've thought about a lot - particularly since the start of the pandemic - is Normal Accidents by Charles Perrow. I almost started my piece on universities during the pandemic - Off Campus - with it. And my earlier piece on the NHS in the pandemic. Resilience is something of a preoccupation of mine. And I think one of Perrow's lessons applies in the case of England's A-level fiasco.

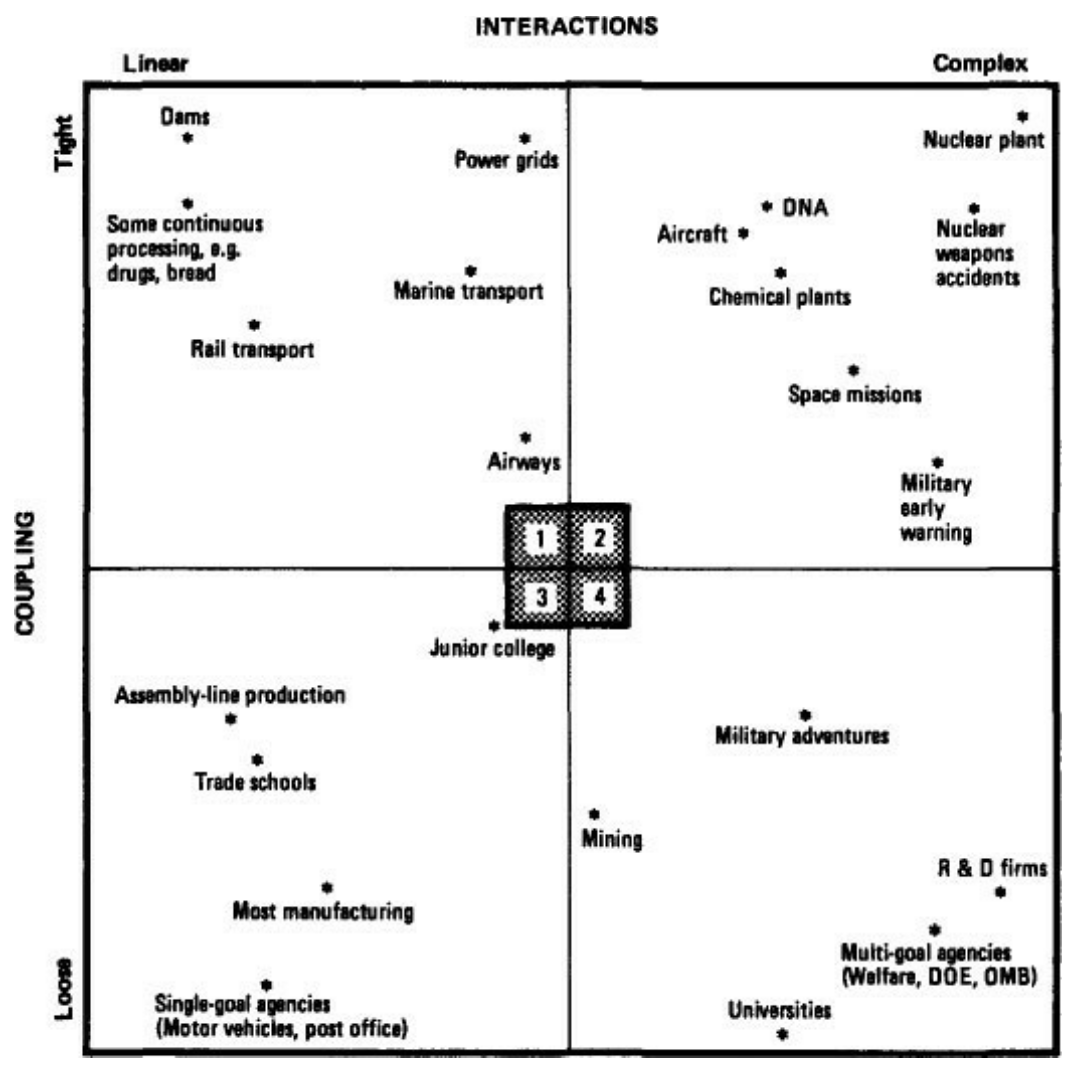

Perrow's core insight is that you can build systems which we can say are vulnerable to sudden collapse - even if we do not know exactly how. The book, somewhere between sociology, engineering and organisational research, explains how systems can be made vulnerable by dint of two pretty simple characteristics.

- The first is "complex interactivity" - the number and degree of system interrelationships in a system. This is really the property by which problems in a system can spread. Take a component that has multiple functions - or which, during a crisis, changes function unexpectedly. A cooling system in a power-plant that fails leading to a fire could be doubly damaging if the system also has flammable parts and starts transmitting flames.

- The second is "tight coupling". The extent to which processes within the system are locked together. Processes which, for example, need to happen in a fixed order, and yet where parts of it "cannot wait or stand by until attended to". A tightly coupled system has little slack, so you cannot pause.

Perrow's point is that when a system has these characteristics, they are vulnerable to catastrophe - even if we think that there are robust safety measures in place. And, indeed, he noted that we had built institutions which had these characteristics where catastrophe is really, genuinely, horrific. The top right quadrant in his schema is pretty frightening.

Perrow's insight is important to seeing the British state's problems with the pandemic. But thinking through the past few weeks, it is pretty apparent that the university admissions process and A-level is a machine built to generate the "normal accidents" that Perrow warns about.

The English A-level and university admissions system has parts that have different functions with different needs - and they interlock and interact:

- The A-level is used as a terminal certificate. For a minority of young people who leave school at 18, it is used as a final exam, and they will use it to get work. It is possible that an A-level will remain in circulation for some years. Hence the obsession with grade inflation: the central mission of Ofqual, the exams regulator, is to fight inflation for these people's benefit.

- The university entry system is used to drive performance in colleges and schools. The government does not have an easy way to hold schools and colleges accountable for the last two years of school - which are optional for students. So it forces universities to give so-called "conditional" offers as the norm. Instead of complicated accountability measures, students are to be told: "You can come to our university if you get three As at A-level".

- The A-level grade is used as a filter to control university sizes. To make conditional offers work, leading universities need to offer more places than they want to give - or the offers cannot be truly conditional. They offer more conditional places than they could honour, knowing that some will not get the grades. This process leans on the fact that the government rations the number of top grades: not everyone getting an offer from UCL or Cambridge can usually make the grades.

This is a complex system: the A-level and the conditional offer system are locked together. But this creates a predictable vulnerability. If there is any event which affects the country for a short spell during exam season - be it power cuts, the death of the Queen or a pandemic - the whole system can be put under strain.

These events could lead to a single-year drop in grade accuracy as exams are cancelled, delayed or disrupted. This year was extreme - and Ofqual sought to award grades using a method with an absurdly low accuracy rate. For most schools, they initially used a terrible, indefensible model that sought to magic information from the ether. When the scale of the inaccuracy became clear, what happened across the UK is pretty predictable. They switched to "centre-assessed grades" - teachers' grades which were neither standardised from centre to centre nor comparable to previous years.

This was a pretty terrible solution: there is literally nothing to stop an A* in one school from being a C in another. But the process worked politically for a simple reason: it awarded higher grades all round. A politically saleable solution to the problem of not knowing if a kid is a B student or an A student is to give them an A. Allow grade inflation. Give the benefit of any doubt. In England, the number of As and A*s rose from 25 per cent in 2019 to 38 per cent of A-levels.

Grade inflation was predictable. It is quite likely that, if we had some kind of testing this year, we'd have ended up doing some inflating, too, when it emerged that the results were skewed by how effectively schools had stayed open. But, in situations where the pupils have not actually had any standardised assessments and so had no ability to influence the outcome, the chain of events from inaccuracy to inflation is even clearer. The politics of defending unjustifiable grade downgrades is rougher when the kids are robbed of their agency.

But the conditional offer process will mean inflation leads to students piling up places in top-choice institutions - and the second-choice places have no-one. The latest admissions data shows admissions high-tariff institutions are up this year by 8 per cent - way higher than they want - because of this year's inflation. Individual universities are talking about taking in an additional 2,000 students this year. You cannot pause, because the results come through in August and term starts in September.

It would not have taken a pandemic to cause this disruption. It was a normal accident. It was waiting to happen.

When you frame the problem in this way, you can see the disaster was coming - and why the government needed to stop the machine.

- If you give grades that are of a higher resolution than the information you actually have on each pupil, then you will be doomed to inaccuracy.

- Inaccuracy at scale will always lead to grade inflation.

- Using university admissions as an incentive structure for sixth form means England cannot absorb grade inflation.

There are answers: abandon grading. Or, if you must award grades in a situation like this, do not pretend they have the same reliability as older grades. You could give people banded grades (maybe "pass", "merit" and "distinction" like the old S-Level) to indicate a change in what is being measured. This would preserve the comparability of grades from year to year by not pretending they are comparable.

Doing this would, at once, also unhook the universities' conditional offer process from the A-level system for a single year. No-one would meet their offers. The universities could then give offers without A-levels. Given that universities already have teacher predictions (and the "A-levels" awarded this year are just teacher predictions passed through a fun-house mirror), the grades contain almost no actual extra information beyond the UCAS form. It would, in Perrow's terms, solve the problem by removing the tight coupling between grades and everything else.

It would mean, in effect, institutions would be required to pick kids based on other information. This is rather better than assigning thousands of young people to institutions by accident, in some cases massively exceeding the universities' capacity, and then letting them work out how to deal with the remainder.

So what about next year? Some of the same issues persist - and some new ones:

- Will we move to norm-referencing (so give out a fixed share of A*s) or criterion-referencing (asking students to meet a standard for each grade)? Will we stick with "comparable outcomes", the process we have used in recent years, which holds grades down unless there is evidence of improvement in overall school standards?

- If we stick with criterion referencing or comparable outcomes, we should expect steep declines in grades: students have lost months of school and will do worse. Is that fair, especially after the bumper crop of high grades in 2020?

- If we go for norm-referencing, do we expect the number of As and A*s to revert to its 2019 levels, or stay at the 2020 level?

- What allowance will be made for the fact that some schools have been able to do very little while some posh kids have kept being taught?

- This is a matter of fairness between candidates. But it is also a hard-headed matter: if the different performance of schools swamps the results, it will kill the usefulness of the exams for spotting kids of different aptitudes (the so-called "predictive validity" of the exams).

- There will be local lockdowns: how will we cope with regional differences in fairness and accuracy? What preparations are being made in case exams are disrupted?

We can say some things. The government should learn something from this fiasco.

- If you do not have the information you need to award normal A-levels, do not try. Award something else. You cannot wish information into being.

- If whatever is awarded is a weak predictor of the relative future performance of the people in this A-level cohort, it will have very little value. And it certainly has no value in HE admissions. So universities should be ditching them anyway, and preparing just to make a slew of unconditional offers.

- Coming up with new admissions systems which use other information would be a good thing anyway. They need a plan for the year after when they will have a cohort of applicants with no reliable GCSE grades and a load of disrupted schooling.

- Maybe a year when A-levels are likely to be pretty useless is the moment to finally ditch pre-qualification admissions altogether. We should look to disassemble the normal accident machine we have built in our education system.

Whatever the answer is, it is not mechanically pretending we have the same information for these cohorts as previous ones. If only the Department for Education had noticed that in March, when they adopted a policy of guessing at the grades people would have attained in a fictional parallel universe. ❦

Chris Cook Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.